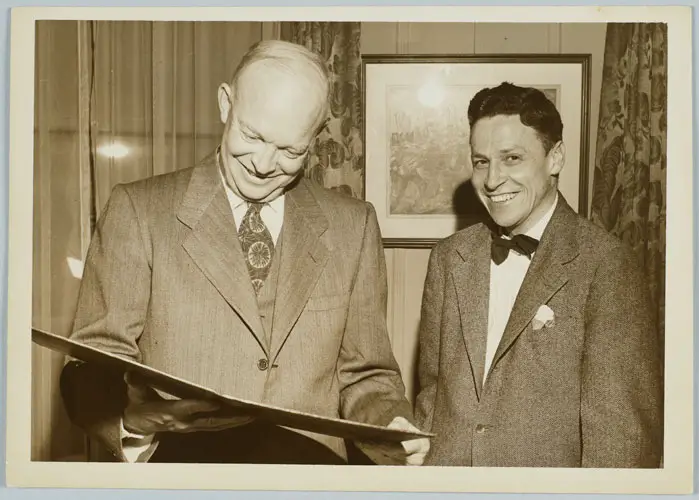

Eugene Jay Sheffer stands out not only for the length of his tenure, lasting nearly a quarter century, from 1942 to 1966, but for the vitality and visibility he brought to the Maison and the notable visitors he welcomed there. Sheffer was passionate about French culture. He had a winning personality—“la gentillesse faite homme,” according to France-Amérique—and became lifelong friends with a number of the visitors he welcomed to the Maison.

Sheffer first came to Columbia College as a freshman in 1922. Handicapped by a neurological disorder and unable to serve in World War II, he was appointed temporary director in 1942 and permanent director four years later. His tenure proved to be among the most interesting periods in the history of the Maison Française. He invited many of the eminent French literary figures of the time, including Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Vercors, Simone de Beauvoir, Eugène Ionesco, Jules Romains, and Georges Simenon. Sheffer also welcomed celebrated performers, such as Louis Jouvet, Charles Boyer, Yves Montand, Simone Signoret, Maurice Chevalier, Jean-Louis Barrault, and Marcel Marceau.

One visitor stood out in particular in Sheffer’s memory, Edith Piaf, who made her first trip to New York in the fall of 1947 for her American debut. When she arrived, Piaf’s impresario, Clifford Fischer, called the Maison Française looking for a tutor to teach “this new French singer” some English. Sheffer jumped at the opportunity and gave the chanteuse two-hour lessons every afternoon for the next three weeks at her suite in the Hotel Ambassador. “My job was to try to get her to say little English résumés as introductions to her French repertoire,” he remembered. “Since she knew no English, the only way to make her repeat these little résumés that I wrote for her was to do it phonetically: she had to imitate me, much in the manner of a parrot.” He helped la môme practice singing “All Dressed Up and No Place to Go” in heavily accented English. After three weeks she was able to say, “Zees ees a song about a fille de joie.” On opening night at the Playhouse, where Piaf debuted with a group of nine French singers called Les Compagnons de la Chanson, Sheffer spotted Maurice Chevalier, Charles Trenet, and Robert Montgomery in the audience. Visiting her dressing room after the show, he met “a very glamorous and beautifully gowned” Marlene Dietrich, who towered over Piaf while congratulating the tiny chanteuse “in very good French.” Sheffer loved the show, but Piaf thought she had done miserably. “When I came on,” she later recalled, “I was wearing my usual little black dress with my mousy hair done up any old way, and my pale face. That was the first disappointment for the Yanks. To them, a star, especially one from Paris, ought to have the means to pay for feathers, sequins and furs. I don’t look anything like a glamour girl! When an American goes out at night, he wants to be entertained. He doesn’t come to a show to hear someone sing about having the blues or being poor. I’d never been in such despair. I’ve suffered when I’ve been in love, but no man ever hurt me like that.” The discouraged Piaf wanted to abandon the tour and pack her bags for Paris. But then a glowing review by music critic Virgil Thomson convinced her to try again at another venue, the Versailles, using a new approach: she would appear alone on stage and she would introduce the songs herself—in English.

Black-and-white photographs of Piaf’s 1947 visit to the Maison Française show her singing and smiling next to the piano, raising her arms expressively, and being surrounded by Sheffer and Les Compagnons de la Chanson. The chanteuse hit it off splendidly with her English tutor, and they became lifelong friends, visiting each other in Paris, Monaco, and New York.

Sheffer made many other friends in his time as director. Jack Kerouac mentions in his autobiography that he worked as Sheffer’s private secretary while he was a student at Columbia. Kerouac helped him edit, translate, and type up the manuscript for his French textbook, and also assisted him in defining words for the daily crossword puzzle that Sheffer published. Kerouac said the two became “fast friends.”

Sheffer also taught in the French Department and edited two books. Aspects de la guerre moderne sur terre, sur mer et dans les airs (1942) prepared students who were studying to become Naval officers. La République du Silence: The Story of French Resistance (1946), edited with New Yorker correspondent A. J. Liebling, was widely adopted for French classes at the college level.

Sheffer was named a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor in 1960 for his activities “furthering Franco-American cultural relations.” In 2006, following the death of Ralph Sheffer, his brother and fellow Columbian, the Sheffer family made a $250,000 gift to endow a lecture series at the Maison Française named for its distinguished former director.